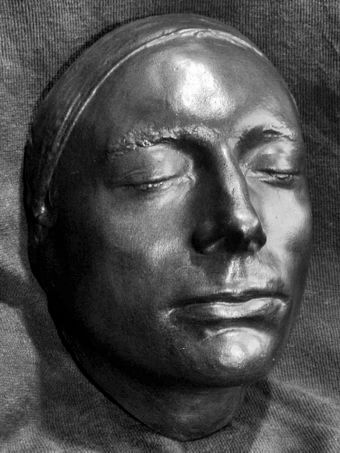

Every day for 30 days we will be featuring a museum object that has inspired or intrigued us, in the hope that “an object a day keeps the doctor away.” We love creating exciting, meaningful storytelling through engaging experiences, but still firmly believe that it is hard to beat the thrill of being in the presence of authentic artefacts. Today’s object is: Keats’ life mask.

On Saturday 14 December 1816, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon made a life mask of Keats. Fellow-poet John Hamilton Reynolds watched the procedure. Keats’s face was greased with fat, straws were put up his nose so he could breathe, and his hair was bandaged. Then he lay on his back and Haydon daubed his face with plaster of Paris, which was left to set for ten minutes or so. Before the invention of photography, this was the only way to get an exact likeness of someone’s face. The resulting life mask (or a replica of it) is on permanent display at Keats House in Hampstead, possibly with the greatest museum label text ever written: PLEASE TOUCH.

Keats House Hampstead (originally Wentworth Place) was the home of John Keats from December 1818 until he left for Rome in August 1820. It was at Wentworth Place that Keats composed the mysterious ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci’, finished the narrative poem The Eve of St Agnes, and wrote his great odes of spring 1819 including ‘Ode to a Nightingale’.

At the beginning of 1820, Keats had begun to develop something of a social life and to enjoy the pleasures of London. On 3 February 1820, he traveled from town, sitting on the outside of the coach to save money without a coat. He stumbled into Wentworth Place at about 11:00 P.M. Brown advised him to go to bed immediately. Brown went to Keats’s room with a glass of spirits, and, as he was getting into bed, Keats coughed and a small spot of blood appeared on the sheet. Brown heard him say, “That is blood from my mouth, bring me the candle Brown, let me see this blood.” And then, looking up at Brown, he said, “I know the colour of that blood; it is arterial blood. I cannot be deceived in that colour. That drop of blood is my death warrant. I must die.” And, indeed, how accurate he was in diagnosis and prognosis, for he died in Rome just over a year later.

Being able to touch Keats’ life mask is a particularly poignant (and strangely tangible) reminder of one of England’s most sensitive minds. As Keats wrote when his own imagination was captured by a Greek urn in the British Museum:

“Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

Keats House is currently closed. Check website for details.