Every day for 30 days we will be featuring a museum object that has inspired or intrigued us, in the hope that “an object a day keeps the doctor away.” We love creating exciting, meaningful storytelling through engaging experiences, but still firmly believe that it is hard to beat the thrill of being in the presence of authentic artefacts. Today’s object is: The Bayeux Tapestry.

Some objects by their very nature tell their own story. Today’s object – The Bayeux Tapestry – is part 1 of 2 such objects. Part 2 is the Chinese scroll Along the River During the Qingming Festival.

This 70-metre long embroidery effectively storyboards the events leading up to the Norman invasion of England by William the Conqueror and the pivotal Battle of Hastings. Dated to the 11th century, it is as close to an eyewitness account as we could hope for. It is also the quintessential primary school project for every English school child and I was lucky enough that my South London state primary school was able to organize a trip to see it in Normandy.

The well-known vignettes from the tapestry are familiar enough – Harold’s oath to William promising him the English crown, Edward the Confessor’s death, the boat building, Haley’s comet, the crossing, the battle itself, William raising his helmet to reassure his troops and King Harold getting the fatal arrow in his eye. Such is the standard stuff of school history books.

But even as primary school kids we were vaguely aware of something subversive about the tapestry. Perhaps it was something about the comic-y format itself. Looking back it was something more. The borders top and bottom begin nicely enough with all sorts of animals and mythical beasts but during the battle itself they are strewn with gory corpses. Little seems glorious about this slaughter and nothing is left to the imagination. It was honest beyond the sanitized pictures in our Ladybird history books. Even the horses are depicted as terrified victims caught up in the mayhem.

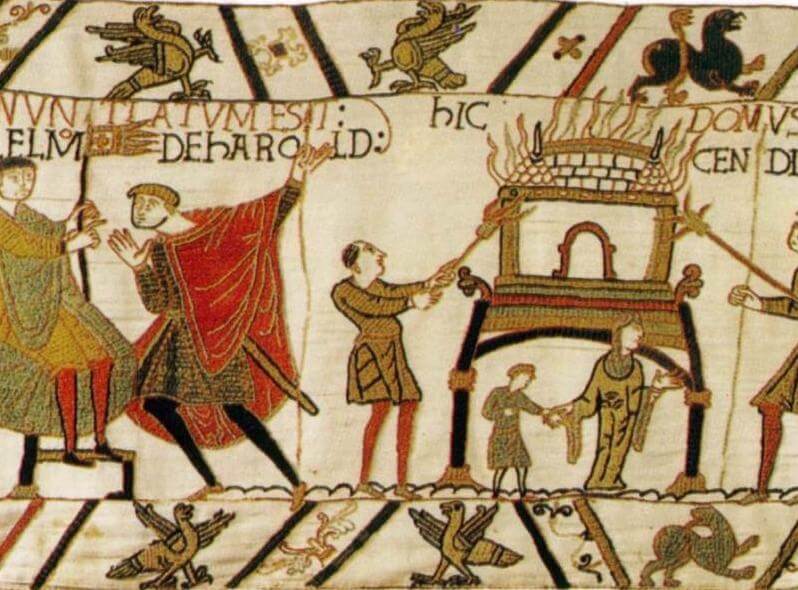

Here is the pity of war in needlework. The scene above shows the arrival on the south coast of England of the Norman invaders, who set about torching the homes of innocent civilians. The woman whose house is being set alight holds her child’s hand. She gestures hopelessly asking the viewer: “Is this just or necessary?”

The Bayeux Tapestry must be one of the most famous, visual examples of the victor writing (or in this case embroidering) the history. Given that it is essentially a justification of the Norman invasion of England, the fact that it treats the enemy Harold and his soldiers with respect and is not shy to imply criticism for actions of its own soldiers is remarkable. The ‘Dark Ages’ may have been brutal but did not lack nuance.

The Bayeux Museum is currently closed. Check the website for details.